Cancer does not travel alone. It sends advance messengers.

Invisible bubbles, thousands of times smaller than the width of a human hair, move through the bloodstream carrying instructions that help cancer colonize new organs.

These microscopic particles may be one of the most important and least understood drivers of metastasis, the process responsible for most cancer deaths.

Now, scientists believe cracking the code of these bubbles could change how cancer is treated.

At the École de technologie supérieure in Montreal, researchers working with specialists from the McGill University Health Centre are zeroing in on how cancer spreads by hijacking the body’s own communication system. Their focus is not on tumors themselves, but on what tumors send out.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Bubbles Cancer Uses to Invade

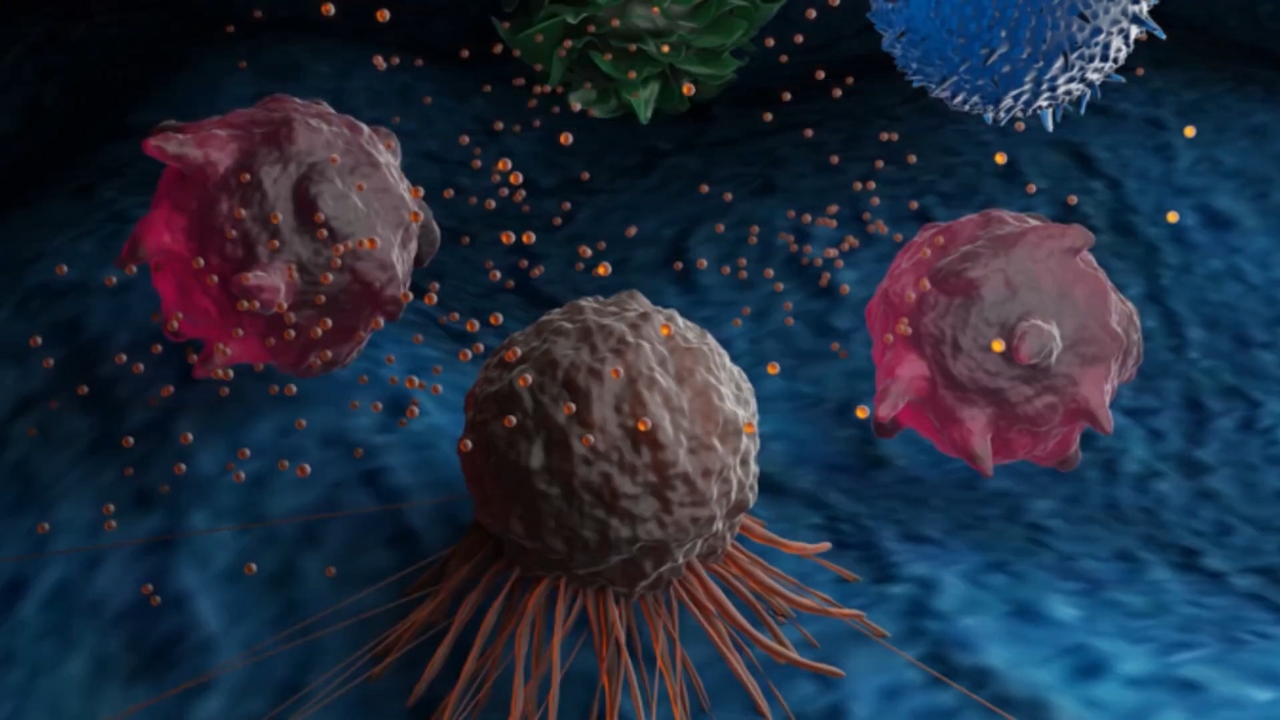

Every cell in the body releases tiny packages called extracellular vesicles. These are lipid-based bubbles filled with proteins and genetic material. In healthy cells, they help coordinate normal biological processes.

In cancer, they become weapons.

When cancer cells release these vesicles into the bloodstream, they can travel to distant organs like the liver or lungs.

Once there, they interact with healthy cells and can alter their behavior, sometimes even changing their DNA. This prepares the ground for new tumors to grow.

This is metastasis at the microscopic level, and it happens long before cancer shows up on a scan.

Why Studying Them is So Hard

Natural extracellular vesicles are extremely difficult to isolate and analyze. They are rare, fragile, and mixed in with countless other particles in the blood.

To solve this, researchers began building their own.

Using micro-scale devices called micromixers, scientists create artificial versions of these vesicles known as liposomes. By carefully combining lipids, proteins, water, and ethanol, they produce bubbles that closely resemble the real thing.

The goal is simple but ambitious. Make fake cancer messengers that behave exactly like the real ones.

Watching Cancer Cells Take The Bait

Once created, these artificial vesicles are introduced to cancer cells grown in the lab. The liposomes are tagged with fluorescent markers, allowing researchers to watch in real time as cancer cells absorb them.

The closer the liposomes match natural vesicles in size and electrical charge, the more readily cancer cells take them in.

This matters because it confirms scientists are recreating the same delivery system cancer uses to spread. It also gives them a powerful tool to test how vesicles influence tumor growth and organ invasion.

Right now, researchers can successfully pack proteins into these liposomes about half the time. Their next milestone is pushing that efficiency close to 90 percent. Animal testing is planned once that threshold is reached.

Turning Cancer’s Trick Against Itself

Understanding how these bubbles work opens the door to stopping them. But it also creates an opportunity to use the same system for treatment.

Liposomes can act as precision drug carriers, delivering medicine directly into cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue. This approach already exists in some treatments, including liposomal forms of chemotherapy drugs like paclitaxel, which improve tolerability and targeting.

Researchers are also experimenting with encapsulating natural compounds such as curcumin, the active ingredient in turmeric. Curcumin has long been studied for its anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects, but it struggles to reach tumors on its own. Inside liposomes, it becomes far more bioavailable.

Scientists are also testing liposomes that carry DNA fragments or antibodies, effectively turning these bubbles into guided missiles for the immune system.

Why This Could Change Cancer Treatment

Most cancer therapies focus on shrinking existing tumors. This research targets something more dangerous: the silent process that allows cancer to spread before it is detected.

If scientists can block or redirect the vesicles cancer cells rely on, metastasis itself could be slowed or even prevented. That would dramatically improve survival rates across many cancer types.

Cancer has been using these microscopic messengers for millions of years. Now researchers are learning its language.

Related Posts:

- A Tiny Gut Molecule Might Cut Type 2 Diabetes Risk,…

- Scientists Put Flu Patients in a Room With Healthy…

- Why This Tiny DNA Clue Could Change Breast Cancer Care

- A Groundbreaking Eye Treatment Just Restored Vision…

- A Common Diabetes Drug May Boost Women’s Chances of…

- Scientists Analyzed 38 Million American Obituaries -…