In January 2026, Havana Syndrome is back in the headlines because reporting says the U.S. government has obtained and tested a portable device capable of generating pulsed radio waves, a mechanism long suspected in the case.

Public details remain limited, and U.S. intelligence agencies have not concluded who, if anyone, used such technology.

Still, the optics matter: for the first time in years, the debate is no longer only about symptoms and theories, but about a physical device investigators believe could plausibly produce the reported neurological effects.

That shift explains why the story is trending again, especially amid heightened U.S. concerns over covert, deniable threats to Americans abroad.

At the same time, the strongest official evidence points in a different direction.

The Intelligence Community’s latest unclassified assessment, updated through December 2024 and released in January 2025, concludes it is very unlikely or unlikely that a foreign actor caused the reported incidents.

NIH-led clinical research published in 2024 found that while affected individuals reported severe symptoms, there was no consistent MRI-detectable brain injury or biological abnormality across cases.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat Havana Syndrome is Called Now, and Why That Matters

Inside government documents, “Havana Syndrome” is increasingly treated as a public label for what agencies call Anomalous Health Incidents (AHIs). That bureaucratic shift matters because it quietly signals uncertainty: AHI is an incident category, not a single confirmed diagnosis with a single proven cause, according to DNI.

In practice, that means one reported “Ahi event” could later be explained as a vestibular migraine, another as a conventional illness plus stress, another as an environmental exposure, and a residual subset might remain unexplained.

The category approach is also why debates have become so circular: people are arguing about “the cause” of something that may not be one thing.

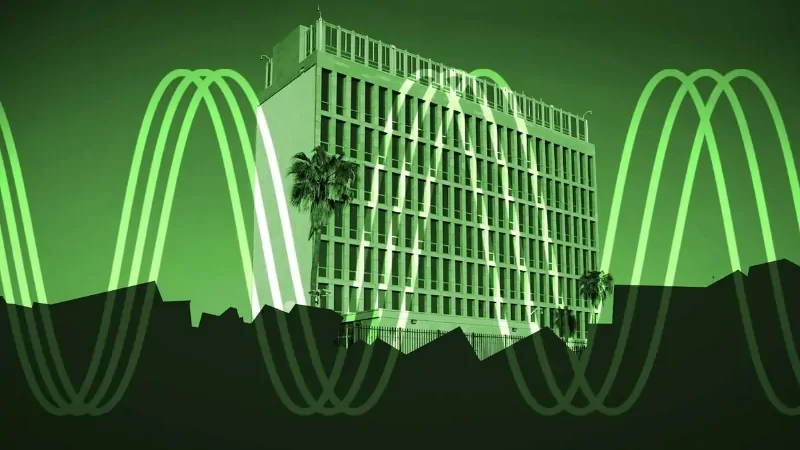

When this first surfaced publicly in 2016 among U.S. Embassy personnel in Havana, the story took on a crisp narrative shape: sudden onset, strange sensory experience, lingering neurological complaints, possible hostile action.

Over time, the global distribution of reports (and the variability in what individuals experienced) turned the problem into something harder to pin down. If your baseline assumption is “one weapon, one actor, one mechanism,” the data can feel frustrating.

If your baseline assumption is “a bucket of different events labeled the same way,” the same data starts to look more plausible, but politically unsatisfying.

The January 2026 Development: The “Portable Device” Storyline, and What is Known so Far

The current wave of attention comes from reporting (summarized widely, including in Scientific American and local outlets carrying CNN material) that the Department of Defense has been testing a device that investigators believe could be linked to Havana Syndrome.

The descriptions that keep recurring are the ones that make headlines: pulsed radio waves, portable or backpack-sized, and acquired via an undercover operation (with reporting also mentioning the Department of Homeland Security in connection with the purchase). Those details, if accurate, do not prove the device caused the historical cases.

But they do change the rhetorical terrain: it shifts the debate from “is a directed-energy device even plausible in the real world” to “what did tests show, what could it do, and can any real incidents be linked to it?”

Two cautions are essential if you want to treat this like a serious story rather than a thriller plot. First, capability is not attribution. A device that can emit pulsed RF energy is not proof that it was deployed against U.S. personnel.

Second, even if a device can produce discomfort or transient effects in controlled settings, the hard part is matching it to the contested claims that shaped the Havana Syndrome narrative: sudden onset at specific locations, consistent symptom clusters, and sometimes long-lasting impairment. That requires event-level evidence, not just general plausibility.

The Official Record: What U.S. Intelligence And U.S. Medicine Have Concluded So Far

If you strip away the noise, the U.S. government’s most authoritative public signals come from two channels: intelligence community assessments and clinical research.

1) Intelligence Community: “Very Unlikely” Foreign Actor, With Documented Dissent on a Small Subset

The ODNI’s unclassified “Updated Assessment of Anomalous Health Incidents, as of December 2024” states that IC components continue to assess it is “very unlikely” or “unlikely” that any foreign actor caused the reported events.

It also notes that some components hold different views about whether a foreign actor might have played a role in a small number of events, which is why the debate never fully dies.

Reuters’ coverage of the 2025 release emphasized the same basic structure: most agencies say “very unlikely,” while one agency judged a “roughly even chance” for a small subset.

2) NIH and Peer-reviewed Work: Severe Symptoms, But No Consistent MRI-Detectable Injury Signature

In March 2024, the NIH publicly summarized results from studies of affected personnel: participants reported severe symptoms, but the research found no evidence of MRI-detectable brain injury or consistent biological abnormalities.

The peer-reviewed publication available via PubMed Central frames the same bottom line: when compared with controls, the study did not find a consistent pattern that would validate a single injury mechanism across cases.

This does not mean patients were “fine” or imagining symptoms; it means the strongest claim often made in popular coverage, a consistent brain injury footprint, did not hold up in that dataset with those methods.

A Timeline That Shows Why The Story Keeps Snapping Back

A timeline is useful here because the “device” news makes more sense when you see how the U.S. government’s interpretation has swung over time.

Year

Key event or finding

Why did it change the debate

2016–2017

Cluster of reports in Havana among U.S. personnel

Establishes the “sudden onset, localized event” narrative

2020

The National Academies report says directed, pulsed RF energy is a plausible mechanism for some cases

Gives the directed-energy hypothesis mainstream institutional backing, while still not proving it

2022

State Department releases redacted JASON report analyzing hypotheses and data limits

Pushes back on broad claims, stresses data quality and constraints, and argues many incidents have mundane explanations

2023

ODNI ICA says foreign adversary involvement is very unlikely

Largest official “downshift” on the foreign-attack narrative (later reaffirmed)

2024

NIH/JAMA work: no consistent MRI-detectable injury signature

Weakens the “consistent brain injury” framing as a general explanation

2024

GAO: patient communication and monitoring problems across pathways

Shifts public focus toward care, access, and system failures, regardless of cause

Jan 2026

Reporting: Pentagon testing a portable pulsed RF device acquired covertly

Re-ignites directed-energy attention by making it about hardware again

What the National Academies And JASON Actually Said, And Why Both Are Still Cited in 2026

One reason Havana Syndrome arguments get so heated is that both “sides” can cite serious institutions. The disagreement is less about whether the symptoms are real and more about whether a specific mechanism is supported by the available record.

The National Academies report (2020) is often cited because it explicitly said that, after considering possible mechanisms, directed, pulsed RF energy was a plausible explanation for certain distinctive acute features.

The Academies also emphasized the human cost and the need for coordinated investigation. That language has been repeatedly recycled in media and advocacy because it is one of the few formal documents that gives directed energy a central role.

The JASON study released by the State Department in 2022 is often cited by skeptics because it stresses limitations: small numbers, inconsistent data products, and lack of a comparable background population.

In a story where people want a single culprit, JASON’s emphasis on “data quality and alternative explanations” reads like deflation, but it is also a reminder that you cannot reverse-engineer a covert attack narrative from symptoms alone.

A fair reading of both is: the Academies argued directed pulsed RF should be taken seriously as a mechanism for a subset, while JASON argued the available data do not support strong claims and that many incidents likely have more ordinary causes. Neither document gives you what the public most wants: a definitive mechanism plus attribution.

The Policy Reality: Congress, Compensation, And Why the U.S. System Treats This as Real Even When The Cause is Disputed

Even as intelligence agencies have leaned away from a foreign campaign explanation, Congress and executive agencies have moved in the opposite direction on one practical point: people reporting AHIs should not be left to fight for care and benefits in a fog of uncertainty.

The HAVANA Act of 2021 created a compensation pathway for certain U.S. personnel with qualifying brain injuries tied to these incidents, and agencies have issued rules and implementation guidance over time.

In 2024, the Department of Defense published an implementation rule that aligns its payment scheme with the State Department’s approach, reflecting the reality that the government expects claims, disputes, and adjudications to continue.

What Patients Reported About the System: The GAO’s View

The GAO report published in July 2024 is blunt about what patients experienced. Based on interviews with AHI patients, GAO describes challenges such as inconsistent support from home agencies, limited information, and unclear points of contact when entering the Military Health System, and difficulties navigating referrals and monitoring.

This kind of finding is not sensational, but it is consequential because it shapes whether affected personnel trust the system and whether claims are handled consistently.

The most important thing to understand here is that “cause uncertainty” does not neutralize harm.

A person can be debilitated by dizziness, headaches, tinnitus, insomnia, and cognitive dysfunction without the government being able to prove a single mechanism. In practice, that means the U.S. system has to operate on two tracks: scientific investigation and patient support.

Oversight reports suggest that the second track has been uneven, which is why Havana Syndrome remains politically alive even when intelligence assessments trend skeptical.

Five Questions That Decide Whether This Becomes a National Security Scandal or a Long Medical-Policy Fight

The reason this story keeps returning is that it sits at the intersection of intelligence culture and medicine. In the U.S., both worlds have strong incentives to avoid admitting uncertainty, but Havana Syndrome forces uncertainty into public view.

Here are the questions that actually matter now, and why they are the ones you will see driving coverage through 2026.

Question

Why it matters in the U.S. right now

What the public record currently supports

Is there a single cause behind most cases?

A single cause would justify a “countermeasures” posture and a clean narrative

NIH and IC records support heterogeneity and uncertainty more than a single unified cause

Could directed pulsed RF explain a subset?

This is the “weapon” hypothesis that drives fear and policy

National Academies treated it as plausible for some; JASON urged caution and emphasized constraints and data limits

Did a foreign actor run a campaign?

This is the threshold for major retaliation logic.

ODNI says very unlikely or unlikely in general; Reuters notes limited dissent for a small subset

Are patients being supported fairly?

Compensation and care become the political battleground when causation is unclear

GAO documents access and communication challenges in the care pipeline

Will the “device” story produce verifiable evidence?

Without verifiable details, it becomes another narrative spike

Reporting says testing is ongoing; official technical details remain limited publicly

FAQ

Bottom Line

@cnn Former CIA agent “Adam” described his experience as Havana Syndrome’s ‘patient zero’ to CNN’s Jim Sciutto, and said he believes the government has downplayed the attack since 2016. The US has spent over a year testing a device purchased in an undercover operation that some investigators think could be the cause of a series of mysterious ailments impacting US spies, diplomats and troops. #cnn #havanasyndrome ♬ original sound – CNN

Solid, as of the current public record, means three things. One, AHIs involve real and sometimes debilitating symptoms in a subset of personnel, and the U.S. government treats the category as serious.

Two, the Intelligence Community’s updated unclassified assessment continues to say it is very unlikely or unlikely that a foreign actor caused the reported events overall, while acknowledging limited disagreement on a small subset.

Three, NIH-led clinical work found severe symptoms but no consistent MRI-detectable brain injury signature or uniform biological abnormality pattern across the studied cohort.

Contested is everything that requires a leap from plausibility to proof: whether directed energy explains a meaningful subset, whether any specific actor did it, and whether any newly discussed device can be tied to real events with attribution-grade evidence.

Related Posts:

- America Is Moving North Again — Here’s Why the…

- Teen Birth Rates by State 2025 – Who's Making…

- Experts Say This Ancient Gene Is Making Pain Feel Worse

- A Tiny Chip the Size of a Grain of Rice Is Helping…

- US Births Fell Again in 2025 as Economic Uncertainty…

- Distracted Driving in Colorado 2026 - Penalties,…