Scientists have identified a promising new method to regenerate cartilage by targeting a single enzyme linked to aging, a finding that could eventually change how osteoarthritis and joint damage are treated.

The study, published in Science, showed that inhibiting an enzyme called 15-PGDH allowed damaged cartilage in mice to regenerate without the need for stem cell therapy.

Although still early-stage research, the results suggest a future where cartilage repair could become less invasive and more biologically targeted than current surgical approaches.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhy Cartilage Damage Has Been So Hard To Treat

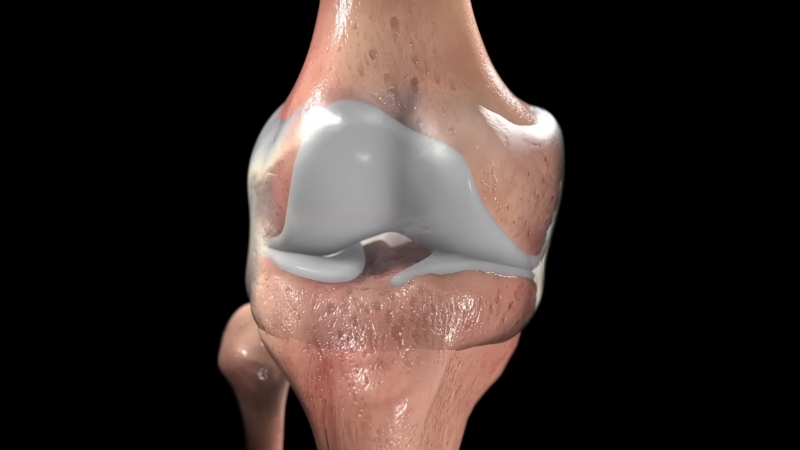

Cartilage plays a crucial role in joint function by providing a smooth, low-friction surface that allows bones to move freely. Unlike many other tissues in the body, cartilage has a very limited ability to heal itself. Once it deteriorates, as often happens with aging or injury, the damage typically becomes permanent.

This progressive loss of cartilage leads to osteoarthritis, one of the most common joint disorders worldwide. The condition causes chronic pain, stiffness, reduced mobility, and, in severe cases, requires joint replacement surgery. Current treatments largely focus on symptom relief rather than true tissue regeneration.

The new research challenges the long-standing assumption that cartilage degeneration is irreversible.

The Role Of The 15-PGDH Enzyme

Researchers discovered that levels of the enzyme 15-PGDH increase with age and following joint injuries. In older mice, the concentration of this enzyme in knee cartilage was roughly double that seen in younger animals. Similar increases are often observed after injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament tears, which frequently precede osteoarthritis in humans.

This enzyme breaks down prostaglandins, molecules involved in tissue repair and inflammation control. Elevated 15-PGDH activity appears to interfere with natural repair processes, contributing to cartilage degradation over time.

Scientists hypothesized that suppressing this enzyme might restore the body’s ability to repair cartilage.

Promising Results In Animal Studies

To test the theory, researchers administered a small-molecule drug designed to inhibit 15-PGDH in aged mice with cartilage damage. Both systemic treatment and localized joint treatment produced encouraging outcomes.

Damaged cartilage began to thicken and regain characteristics of healthy tissue. Importantly, the regenerated material was hyaline cartilage — the same smooth, durable type found in healthy joints rather than scar-like fibrous tissue.

Researchers described the transformation as notable because true cartilage regeneration has historically been extremely difficult to achieve.

A Shift Away From Stem Cell Strategies

Most previous attempts to regenerate cartilage have focused on stem cell therapy, which aims to introduce new cells capable of rebuilding tissue. This approach can be complex, expensive, and sometimes unpredictable.

The new study suggests a different pathway. Instead of adding new cells, scientists found they could effectively “reprogram” existing cartilage cells.

When the 15-PGDH enzyme was inhibited, cells that previously contributed to tissue breakdown shifted toward repair functions.

Gene activity patterns changed in ways that favored cartilage maintenance and rebuilding. Cells responsible for cartilage degradation declined, while cells involved in healthy cartilage formation nearly doubled.

This indicates that the body may already have the tools needed for repair — they simply need the right biochemical environment.

Early Signals In Human Cartilage Samples

Researchers also tested the enzyme inhibitor on human cartilage samples collected during knee replacement surgeries.

After about one week of treatment, the samples showed reduced enzyme activity, less tissue breakdown, and early signs of extracellular matrix rebuilding.

The extracellular matrix is critical for cartilage strength, elasticity, and shock absorption. Although these findings do not yet translate into clinical treatment, they provide preliminary evidence that similar mechanisms might operate in human joints.

Potential Impact On Osteoarthritis Treatment

If future clinical trials confirm these findings, targeting 15-PGDH could represent a major shift in osteoarthritis therapy. Instead of focusing mainly on pain relief, injections, or joint replacement surgery, treatment might aim directly at restoring cartilage health.

Possible advantages include:

However, researchers caution that human clinical trials are still needed before any treatment becomes widely available.

What Comes Next In Research

The next phase will likely involve safety studies, dosage optimization, and eventually controlled clinical trials in humans. Scientists will need to confirm that enzyme inhibition produces similar regenerative effects in people and does so safely over the long term.

Researchers are also exploring whether similar strategies might work for other aging-related tissue degeneration beyond joints.

A Growing Shift Toward Regenerative Medicine

@drbenmiles A Kneat Discovery 🦴 #medicine #discovery#sciencetok #fyp #foryoupage ♬ original sound – Dr Ben Miles

This discovery fits into a broader trend in medicine focusing on regenerative approaches rather than purely symptomatic treatment. Scientists increasingly aim to restore normal biological function rather than simply manage damage.

While cartilage regeneration without stem cells is not yet ready for clinical use, the findings represent a significant conceptual advance. They suggest that aging tissues may retain hidden regenerative potential that can be activated through targeted molecular interventions.

Related Posts:

- Scientists Find a Way to Help Aging Cells “Swap…

- A Groundbreaking Eye Treatment Just Restored Vision…

- Scientists Just Reversed Vision Loss in Mice, Humans…

- Why This Tiny DNA Clue Could Change Breast Cancer Care

- Climate Change Could Kill 500,000 More People…

- First Case of Type 1 Diabetes Reversal Achieved with…