Pancreatic cancer has long been one of oncology’s most unforgiving diagnoses. For most patients, it is discovered late, resists treatment, and offers little time.

Survival rates have barely moved in decades, even as other cancers have seen steady gains.

That is why a new immune cell therapy now entering clinical trials is drawing careful attention. Early results suggest it may extend survival for some patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, offering something this field rarely delivers: cautious but credible hope.

The approach builds on CAR T cell therapy, an immunotherapy that has already transformed treatment for certain blood cancers. Until now, those successes have largely stopped at solid tumors. Pancreatic cancer, in particular, has proven stubbornly resistant.

Why Pancreatic Cancer Defies Treatment

Pancreatic cancer begins in the pancreas, an organ essential for digestion and blood sugar regulation. Symptoms often appear only after the disease has spread, ruling out surgery for most patients.

Chemotherapy remains the standard option, but even aggressive drug combinations usually buy only limited time.

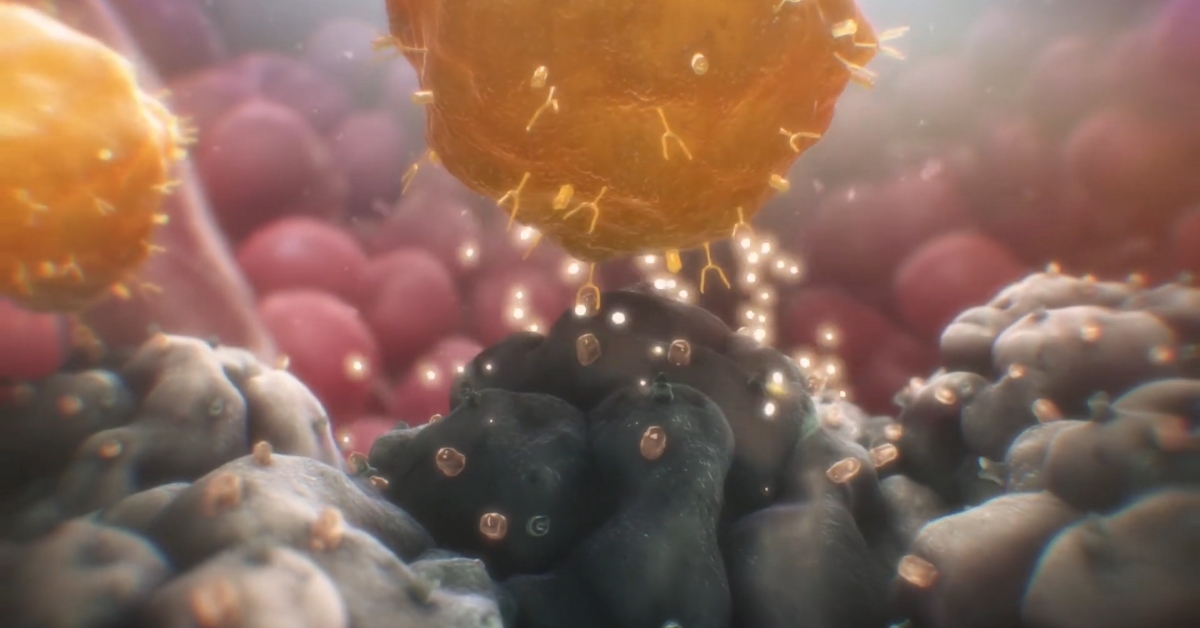

One reason pancreatic cancer is so hard to treat is its physical structure. Tumors form dense, fibrous barriers that block immune cells from entering. Blood vessels within the tumor are abnormal and inefficient, further limiting access.

At the same time, pancreatic cancer cells are difficult to distinguish from healthy tissue. They often lack a single, clear molecular target, raising the risk that immune therapies could miss the cancer or damage normal cells instead.

These challenges have repeatedly frustrated attempts to apply immunotherapy to pancreatic tumors.

How CAR T Therapy Works, and Where It Struggles

CAR T therapy works by collecting a patient’s own immune cells from the bloodstream, genetically engineering them to recognize cancer cells, and then infusing them back into the body. Once returned, these cells act as living drugs, hunting down and destroying tumors.

The approach has been highly effective in certain leukemias and lymphomas. Solid tumors are another story.

Tumor cells can change over time, shedding the molecular markers targeted by therapy. When that happens, immune cells lose their ability to recognize the cancer. In pancreatic cancer, this adaptability has been a major obstacle.

As William A. Haseltine, Ph.D., describes in his work on immune cell therapy, overcoming these barriers is essential if CAR T is to succeed beyond blood cancers.

A Multi Target Strategy Changes the Equation

The new therapy under investigation takes a different approach. Instead of training immune cells to recognize a single tumor marker, researchers engineered them to target five at once.

These markers – PRAME, SSX2, MAGEA4, NY-ESO-1, and Survivin – are commonly expressed across pancreatic tumors. Laboratory analysis shows that most pancreatic cancers express at least two of them.

By targeting multiple antigens simultaneously, the therapy reduces the cancer’s ability to escape detection. Even if tumor cells lose one marker, others remain available for immune attack.

This multi-antigen strategy represents a significant shift in how CAR T therapy is applied to solid tumors.

What Early Trial Results Show

The treatment is currently being tested in an early-phase clinical trial involving patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Participants receive immune cells engineered to recognize the five tumor-associated markers.

Imaging from the study shows shrinkage not only in primary pancreatic tumors but also in metastases to the liver and lymph nodes. Equally important, the therapy appears to be safe so far, with immune cells persisting in the body after treatment.

While the trial is still in its initial stages, patients appear to live longer than expected based on historical outcomes with standard chemotherapy alone. Researchers also report sustained levels of tumor-targeting immune cells months after infusion.

The study was published in Nature Medicine, adding weight to the findings and signaling serious scientific scrutiny.

Combining Immune Therapy With Other Treatments

Researchers are also exploring how this therapy might work alongside existing treatments. Chemotherapy, for example, may help weaken tumor defenses, making it easier for immune cells to enter.

Other agents may improve blood flow within tumors or reduce the physical barriers that block immune access.

These combination strategies could further increase effectiveness, particularly in cancers as complex as pancreatic tumors.

What This Means for Patients

@keckschoolusc How are pancreatic cancer therapies evolving through research? Steven Grossman, MD, PhD, with USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, shares his lab’s research into new therapy methods.💜⚕️ #PancreaticCancer #PDAC #CancerTherapy #Immunotherapy #Cancer #CancerPatient #CancerSurvivor #CancerResearch #MedicalResearch #MedicalFacts #MedicalTikTok #MedTok #Health #Wellness #LearnSomethingNew #USC ♬ Echos in My Mind (Lofi) – Muspace Lofi

It is too early to call this a cure. Larger trials are needed to confirm survival benefits, identify which patients respond best, and understand long-term effects.

Still, the results exceed early expectations in a field where progress is often incremental at best. By targeting multiple tumor markers at once, this therapy addresses one of the central reasons immunotherapy has struggled in pancreatic cancer.

For patients facing a disease with few options and grim statistics, even modest gains matter. This approach may not only improve outcomes for pancreatic cancer but also open the door to similar strategies against other hard-to-treat solid tumors.

For the first time in years, pancreatic cancer research is offering something more than incremental change. It is offering a new direction.

Related Posts:

- How Clinical Laboratories Are Adapting to the Rise…

- Teen Birth Rates by State 2025 – Who's Making…

- Eidetic Memory - How Rare Is It and Who Really Has It?

- Why Children With This Rare Mutation Lose Brain…

- The State with the Fewest People Is One of the Biggest

- One in Four Teens Use ChatGPT for Homework - Experts…