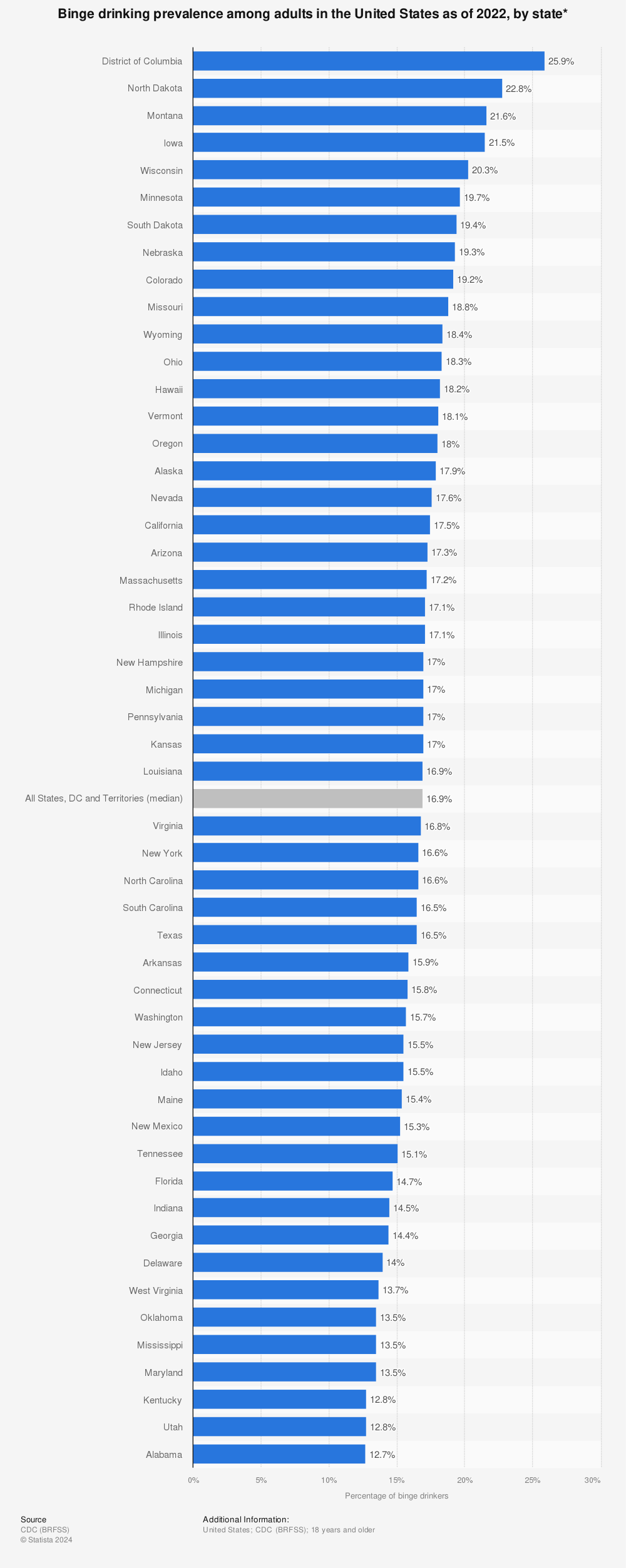

Alcohol misuse remains one of the most persistent public health issues in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2023 BRFSS data), more than 17% of U.S. adults report binge drinking at least once in the past month, and in some states the share is above 20%. If we expand the lens to clinical Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD), the medical definition of “alcoholism” used by the DSM-5, then the most recent SAMHSA National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH, 2022–2023, released February 2025) confirms that the Upper Midwest, Plains, and Mountain West continue to show some of the country’s highest burdens.

Table of Contents

ToggleKey Takeaways

- North Dakota, Iowa, South Dakota, Montana, and Nebraska have the highest binge-drinking rates among states.

- Washington, D.C., while not a state, has the single highest rate in the nation at nearly 28%.

- For alcohol-related deaths, New Mexico still leads, with more than 84 deaths per 100,000 residents in 2023, roughly double the national average.

Binge Drinking: Where It’s Most Common

Find more statistics at Statista

Binge drinking is often used as a proxy for alcohol misuse because it’s easy to measure in surveys and closely linked to health and social harms. CDC data for 2023, the most recent finalized numbers, show clear geographic clustering.

Why here? According to CDC researchers, cultural norms around heavy drinking in the Midwest and Northern Plains, combined with fewer urban restrictions and long winters that drive social drinking indoors, help explain these numbers. States like Wisconsin, North Dakota, and Iowa also have long-standing reputations as “beer states,” which the data continue to confirm.

Environmental factors also play a role. In regions like North Dakota, Montana, and South Dakota, long winters and rural isolation mean fewer entertainment alternatives outside of alcohol-centered gatherings. Research from the NIH highlights that rural counties often lack affordable recreation, which makes drinking one of the dominant leisure activities.

At the same time, state-level policies vary widely. States with lower alcohol excise taxes and fewer restrictions on sales (such as Wisconsin and Iowa) create easier access, which has been linked by public health researchers to higher binge drinking prevalence. Contrast this with states that enforce stricter liquor laws or higher taxes, like Utah or Massachusetts, where binge drinking rates are far lower.

Demographics matter too. Young adult populations, particularly in college-heavy states like Iowa, contribute significantly to binge drinking statistics.

In short, the data reveal that binge drinking is not an isolated behavior but a cultural pattern tied to tradition, climate, economics, and regulation. That’s why North Dakota, Iowa, and Wisconsin consistently appear near the top of these rankings year after year, because the social fabric around drinking is deeply entrenched.

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD): The Clinical View

What really signals alcoholism in the medical sense is Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD), a clinical diagnosis based on patterns of dependency, loss of control, and continued drinking despite harm. According to the 2022–2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), released by SAMHSA in February 2025, an estimated 28.8 million Americans aged 12 and older met the criteria for AUD. That’s close to 1 in 11 people, underscoring how widespread the problem has become.

The burden, however, is not evenly distributed. States across the Northern Plains and Mountain West stand out with rates well above the national average. In places like Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Alaska, survey estimates suggest that nearly 1 in 8 adults (12–13%) could be classified as having AUD. This is significantly higher than the national average of roughly 9%. These states not only have high rates of binge drinking but also show signs of deeper, long-term dependency that affects families, workplaces, and healthcare systems.

Why here? Several factors converge. First, cultural norms in rural communities often normalize heavy drinking as a form of social bonding. Second, geographic isolation means fewer treatment facilities, which makes recovery harder to access. According to SAMHSA, some rural counties in Montana and the Dakotas have no specialized addiction services within 100 miles.

For men in particular, who often face barriers to seeking help due to stigma or cultural expectations, programs designed specifically for them can make a major difference. Addiction treatment centers like Mountain Valley Recovery highlight how men ’s-only treatment centers provide targeted support that aligns with the unique social and psychological challenges men face when addressing addiction.

Alcohol-Related Deaths: Where Harm Is Greatest

| State | Alcohol-Attributable Death Rate (per 100k, 2023) |

| New Mexico | 84.5 |

| Alaska | 65+ |

| Wyoming | 62+ |

| Montana | 60+ |

| South Dakota | 58+ |

| National Average | ~42 |

If AUD shows how many people are struggling, alcohol-related mortality shows the human cost. Nowhere is this clearer than in New Mexico, which has led the nation in alcohol-related deaths for years. According to the New Mexico Department of Health (2023), the state recorded an alcohol-attributable death rate of 84.5 per 100,000 residents, almost double the U.S. average of 42.

Why this matters: NM, where drinking kills 2000+ people/year, has a higher alcohol-related death rate than any other state. Alcohol is also a billion $ business there. And for decades, electeds have acted to bolster its sales rather than reduce its harms. https://t.co/rFCeLvzYX3

— Ted Alcorn (@tedalcorn.bsky.social) (@TedAlcorn) February 9, 2024

Other states in the Mountain West and Northern Plains also rank alarmingly high. Alaska, Wyoming, Montana, and South Dakota all post mortality rates between 58 and 65 per 100,000, placing them well above the national average. These figures are not just statistics; they reflect thousands of lives lost annually to liver disease, drunk-driving crashes, alcohol poisoning, and alcohol-linked cancers.

New Mexico’s unique challenges help explain its grim distinction. The state struggles with persistent poverty, limited access to healthcare in rural areas, and cultural acceptance of drinking across generations. Public health officials also note that alcohol outlets are widespread and alcohol taxes remain low, making cheap liquor accessible even in the poorest communities. These structural factors make alcohol misuse both more common and more deadly.

By contrast, states with stricter policies, such as higher alcohol taxes, reduced sales hours, or stronger enforcement of DUI laws, tend to have much lower death rates. For example, Utah, which has some of the strictest alcohol regulations in the country, consistently reports among the lowest alcohol-related mortality rates. This contrast underscores how policy decisions and cultural attitudes directly shape public health outcomes.

Why Certain States Struggle More

Several overlapping factors drive these differences:

- Culture and Social Norms – Midwest “drinking cultures” normalize heavy use. Wisconsin and Iowa are examples where beer consumption is embedded in sports, college life, and community events.

- Rural Access to Care – States like Montana and South Dakota have sparse populations, making treatment and recovery services difficult to access.

- Economic Stressors – Regions with higher poverty or unstable employment often see higher alcohol misuse.

- Policy Environment – States vary in excise taxes, alcohol outlet density, and enforcement of drunk-driving laws, all of which influence outcomes.

Conclusion

According to the CDC, SAMHSA, and state health agencies, alcoholism in 2025 is far from evenly spread across the United States. The Upper Midwest and Mountain West stand out for high binge drinking and AUD prevalence, while New Mexico remains ground zero for alcohol-related deaths.

The data show that alcohol misuse is not just a matter of personal choice—it reflects culture, geography, and policy. For public health leaders, these numbers underline the urgent need for tailored strategies: rural treatment expansion in the Plains, targeted education in college-heavy states, and stronger mortality reduction efforts in New Mexico.

Related Posts:

- US States With the Highest Homeowners Insurance…

- The 8 States With the Highest Car Accident Fatality…

- Bipolar Disorder Hospitalizations 2025 - Which…

- Top 5 States With the Highest Demand for Registered…

- 10 Highest-IQ States in the US for 2025 - What the…

- US States with the Highest and Lowest Dental Care…