Mental illness is a pervasive public health challenge – approximately 1 in 4 U.S. adults experiences a diagnosable mental disorder in any given year, according to hopkinsmedicine.org.

Among these conditions, bipolar disorder – a chronic mood disorder characterized by alternating episodes of mania and depression – affects about 2.8% of American adults (roughly 7 million people), according to National Institute of Mental Health estimates.

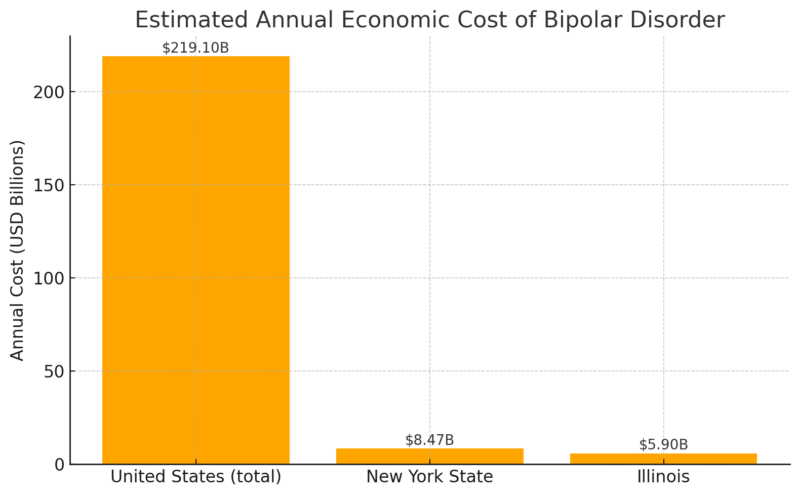

The human and economic toll of bipolar disorder is immense. A recent analysis put the annual economic burden of bipolar disorder at $219 billion in the U.S., a figure that encompasses both direct medical costs and substantial indirect costs from lost productivity.

This makes bipolar disorder one of the costliest mental health conditions, comparable to diseases like diabetes (which costs ~$333 billion annually) despite diabetes affecting a much larger share of the population, according to ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Bipolar patients face higher rates of unemployment, work impairment, and healthcare utilization than the general population, underscoring the far-reaching impact of this illness.

Table of Contents

ToggleKey Takeaways

Need for Action

Journal Bipolar Disorders notes that equally alarming is the heightened suicide risk associated with bipolar disorder. It is among the most lethal psychiatric disorders, with research indicating bipolar patients have a 20–30 times greater suicide rate than the general population.

An estimated 4–19% of individuals with bipolar disorder ultimately die by suicide, and up to 50% will attempt suicide at least once in their lifetimes. (For comparison, about 45,000 Americans die by suicide in a typical year, according to cdc.gov.)

This staggering risk makes suicide prevention and effective treatment in bipolar disorder a pressing priority. Indeed, bipolar disorder accounts for a disproportionate share of overall suicides each year, reflecting the severe outcomes that can occur without adequate care.

Prevalence and Impact of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is relatively less common than some other mental illnesses, but its prevalence still translates to millions of Americans. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) and other epidemiological studies provide detailed insights into how bipolar disorder affects different demographic groups:

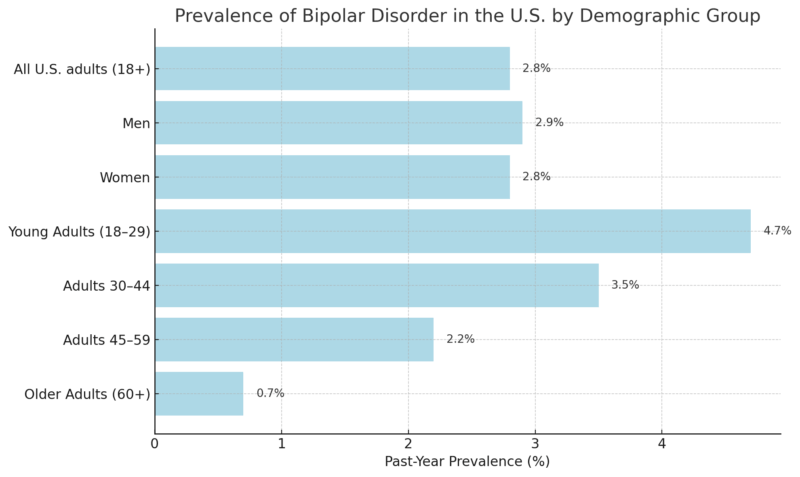

- Overall Prevalence: About 2.8% of U.S. adults had bipolar disorder in the past year, and approximately 4.4% will experience it at some point in their lifetime. This means roughly one in every 35 adults lives with bipolar disorder in a given year.

- By Gender: Bipolar disorder appears to affect men and women at roughly equal rates. In the Hopkins data, 2.9% of men and 2.8% of women were affected in 12 months. Unlike major depression (which is almost twice as common in women), bipolar illness does not show a strong gender disparity.

- By Age: Bipolar disorder often begins in young adulthood, and prevalence is highest in younger age brackets. Among adults aged 18–29, about 4.7% had bipolar disorder in the past – the highest of any age group. Prevalence then declines with age: it was 3.5% for ages 30–44, about 2.2% for ages 45–59, and under 1% (around 0.7%) among seniors 60 and older. This pattern reflects the typical onset of bipolar disorder in the late teens or 20s, with fewer new cases arising in older age, as well as the increased mortality and misdiagnosis that affect older patients.

- By Race/Ethnicity: Epidemiological surveys have generally found no major differences in bipolar disorder prevalence by race or ethnicity. Lifetime prevalence is in the same approximate 2–4% range for Black, Hispanic, and White Americans, indicating that bipolar disorder affects all racial groups at similar rates. However, it’s important to note that diagnosis rates in clinical practice can differ due to disparities (discussed later). For instance, Black individuals are more likely to be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia when they have mood disorders, which historically led to undercounting bipolar cases in that population.

Prevalence of Bipolar Disorder in the U.S. by Demographic Group

Beyond prevalence, bipolar disorder imposes a heavy burden on individuals, families, and society. Notably, it often causes severe functional impairment.

Bipolar disorder has one of the highest rates of serious impairment among mood disorders – in one national survey, about 83% of adults with bipolar disorder were classified as having “serious” impairment in their daily functioning, versus 17% with moderate impairment.

This level of disability stems from the extreme mood swings, cognitive effects, and behavioral impacts of the illness, which can disrupt a person’s ability to maintain employment, relationships, and self-care.

Economic costs of bipolar disorder are accordingly enormous. Recent estimates (in 2018 dollars) put the total annual cost at roughly $200–$219 billion in the United States. To put this in perspective, bipolar disorder’s economic burden is on par with or greater than many physical illnesses that have higher prevalence.

For example, the total yearly cost of diabetes (which affects about 9–10% of adults) is around $333 billion; bipolar disorder (affecting ~2–3% of adults in a year) costs only somewhat less than that. This indicates a very high cost per patient. Indeed, one study calculated an average annual cost of ~$88,000 per person with bipolar I disorder, once factoring in medical care, lost productivity, and other expenses.

A major share of the bipolar economic burden comes from indirect costs. As shown in prior analyses, roughly 72–80% of the total cost is attributed to indirect factors such as lost productivity, unemployment, caregiving burdens, and premature mortality.

In one breakdown, of ~$158.5 billion per year in indirect costs for bipolar I patients, over half (50%) was due to unemployment, ~34% due to productivity loss among caregivers (family members who must reduce work to provide care), and nearly 9% due to work loss from premature deaths (suicides or medical mortality) in bipolar patients.

Direct medical costs (hospitalizations, outpatient care, medications) make up the remaining fraction, on the order of 20–28% of the total. These direct costs are still substantial (tens of billions of dollars nationally each year), due in part to the frequent need for hospital stays during severe mood episodes and the chronic nature of treatment (lifelong management with mood stabilizers, therapy, etc.).

It’s also instructive to consider the economic burden at the state level, since prevalence and spending can vary by state. Table 2 presents some examples of state-specific annual costs of bipolar disorder, illustrating the scale of the financial impact in both large and mid-sized states (figures include both direct and indirect costs where available):

Estimated Annual Economic Cost of Bipolar Disorder – U.S. vs. Selected States

As shown above, major states incur multi-billion-dollar costs each year related to bipolar disorder. New York, for example, was estimated to spend or lose over $8 billion in a single year due to bipolar disorder’s impact, according to laopcenter.com. Illinois likewise incurs on the order of $6 billion in annual costs associated with bipolar illness.

These costs include healthcare utilization (e., psychiatric hospital stays, emergency visits, medications) as well as indirect losses like reduced workforce participation and increased disability payments.

States with larger populations, of course, have higher absolute costs, but the burden is also influenced by factors like the state’s prevalence rate, the effectiveness of its mental health services, and social factors (poverty, insurance coverage, etc.).

The high economic burden underscores why bipolar disorder is sometimes called an “illness of mass destruction” – not for its prevalence, but for its capacity to derail lives and strain health systems and economies.

Beyond dollars, the human impact of bipolar disorder is profound. The illness often strikes early in life (average onset in the early 20s) and can cause recurrent episodes that disrupt the formative years of education and employment.

People with bipolar disorder face elevated rates of other challenges as well, including co-occurring substance use disorders (self-medicating with drugs or alcohol is not uncommon), and comorbid anxiety disorders, which can complicate treatment.

Perhaps most sobering is the toll in lives: suicide is a leading cause of death among people with bipolar disorder. Studies have found that bipolar disorder has one of the highest suicide attempt rates of any psychiatric condition. As mentioned, up to half of patients attempt suicide, and roughly 1 in 5 may die by suicide if effective intervention is not in place.

Science Direct notes that this is reflected in national suicide statistics – despite comprising only a few percent of the population, individuals with bipolar disorder (especially bipolar I) are thought to account for a significant fraction of all suicide deaths.

Each suicide and suicide attempt represents an immeasurable personal and family tragedy, reinforcing the importance of accessible treatment (such as mood stabilizing medications, psychotherapy, and crisis services) and early intervention for those at risk.

State-by-State ER Admission Rates for Bipolar Hospitalizations

When symptoms of bipolar disorder become extreme, such as a dangerously manic episode or a suicidal depressive episode, hospitalization is often required to stabilize the patient. Hospital admission rates for bipolar disorder can serve as one indicator of the acute burden of the illness in different regions.

Here we examine state-by-state data on inpatient stays for bipolar and related disorders, primarily drawing on a comprehensive report from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Statistical Brief #288, which analyzed mental health hospitalization rates across 38 states.

The table below ranks states by their rate of bipolar-related hospitalizations (inpatient stays) per 100,000 population, averaged over. (Only states that provided data to HCUP are included – 38 states in total – so some states are not listed, and this is the most recent data.)

The rates reflect hospital stays where the principal diagnosis was bipolar disorder or related mood disorders, essentially capturing serious episodes requiring inpatient care.

Higher rates can indicate a combination of factors: higher prevalence or severity of bipolar illness in the population, greater availability of psychiatric hospital services, and/or differences in care practices (for example, some states might hospitalize patients more readily, whereas others rely on outpatient crisis services or have fewer psych beds available).

Rank

State

Hospitalization Rate per 100,000

1

Illinois

150.6

2

Nebraska

140.4

3

West Virginia

139.7

4

Maryland

128.8

5

Rhode Island

127.6

6

New Jersey

121.7

7

Pennsylvania

117.2

8

Florida

109.1

9

Tennessee

98.7

10

Massachusetts

93.6

11

Louisiana

92.3

12

New Mexico

92.5

13

Mississippi

66.5

14

Iowa

87.5

15

Michigan

87.5

16

Indiana

84.4

17

Minnesota

84.4

18

Montana

84.3

19

North Carolina

94.2

20

Utah

74.2

21

Oklahoma

71.0

22

Kentucky

70.0

23

North Dakota

65.2

24

Arkansas

79.8

25

Wisconsin

58.1

26

South Carolina

46.0

27

Georgia

51.8

28

Missouri

(Data not available)

29

Oregon

49.1

30

New York

(Data not available)

31

Hawaii

49.3

32

Texas

45.0

33

Wyoming

45.0

34

Delaware

37.4

35

Nevada

68.7

36

Colorado

35.9

37

Arizona

47.1

38

Washington

33.2

Looking at this ranking, we see dramatic variation among states. The national average rate of bipolar hospitalizations was about 83.6 per 100,000 population in that period. However, individual states ranged from roughly 33 per 100,000 (the lowest) up to 150 per 100,000 (the highest) – a difference of almost fivefold.

The highest hospitalization rates for bipolar disorder were observed in a cluster of states led by Illinois, which had about 150.6 hospital stays per 100,000 people, the highest of all states analyzed. Following Illinois were Nebraska (approximately 140.4 per 100k) and West Virginia (~139.7 per 100k), all far above the national average.

Rhode Island and Maryland also ranked in the top five with rates around 127–129 per 100k. These figures indicate that in those high-ranking states, bipolar disorder leads to frequent hospitalization relative to other states.

For example, Illinois’s rate (150.6) is nearly four times that of the lowest state and implies a significant burden on Illinois hospitals and communities. (Later, we will explore why certain states like Illinois and Nebraska have such high rates – it may relate to underlying prevalence, but also to how care is organized regionally.)

On the other end, the lowest hospitalization rates were recorded in states like Washington, Colorado, and Delaware, with Washington State being lowest at only 33.2 bipolar stays per 100k. Delaware (37.4) and states such as Arizona (47.1) and Texas (45.0) were also among the lowest tier.

It’s notable that Texas, despite its large population and many urban centers, had one of the lowest reported hospitalization rates for bipolar disorder (around 45 per 100k). Colorado had about 35.9 per 100k, making it the second-lowest after Washington in this dataset.

These low numbers might superficially suggest “healthier” populations, but as we will discuss, low hospitalization rates can sometimes signal barriers to care or under-utilization of hospital services for mental health, rather than an absence of bipolar cases.

A separate analysis highlighted that Delaware, Texas, and Washington consistently had among the lowest rates for all five leading mental health inpatient diagnoses (including bipolar, depression, schizophrenia, etc.). This pattern raises questions about whether those states have fewer psychiatric beds or different approaches that keep hospitalization rates down.

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Disparities

While bipolar disorder affects all demographics relatively equally in prevalence, significant disparities exist in how the disorder is diagnosed and treated across different groups. These disparities can influence hospitalization rates and outcomes.

One major concern is the misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder in minority populations, especially Black/African American patients. Symptoms of bipolar disorder (like mood swings, agitation, or even psychotic features during mania) can sometimes resemble or co-occur with symptoms of other disorders.

Studies have shown that Black individuals with bipolar disorder are far more likely to be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia compared to White individuals.

In a 2018 systematic review, clinicians appeared to overemphasize psychotic symptoms in Black patients and overlook mood symptoms, leading to incorrect schizophrenia diagnoses. This mislabeling has serious consequences: a patient misdiagnosed as schizophrenic often does not receive appropriate mood stabilizers or therapy for bipolar disorder.

As one psychiatrist noted, if you’re Black and misdiagnosed, “you don’t get the full gamut of psychotherapy and medications [for bipolar disorder]”. Instead, the treatment might focus on antipsychotic drugs alone, which is incomplete for bipolar (where mood stabilizers like lithium or anticonvulsants are standard).

Misdiagnosed patients can suffer worsening of their actual condition and more frequent hospitalizations. A famous case series in 1980 documented Black patients with bipolar disorder who had been misdiagnosed with schizophrenia – they experienced years of disabling symptoms and repeated hospital stays until the correct diagnosis was made and mood stabilizing treatment started, after which their conditions improved.

This disparity in diagnosis isn’t limited to Black patients. Latino patients with mood disorders have also been subject to misdiagnosis; one study found that Latinos presenting with psychotic symptoms were more likely to receive a diagnosis of major depression (instead of bipolar or schizoaffective), compared to White patients.

Overall, minority patients often face cultural and communication barriers in psychiatric evaluation, and clinician biases (conscious or not) can lead to interpreting their symptoms differently.

There’s also the issue of distrust and reduced help-seeking – some minority communities may be less likely to seek psychiatric care early, leading to more severe presentations when they do get care.

When it comes to treatment access and quality, the disparities are stark. Under-treatment in minorities is a well-documented problem in bipolar disorder.

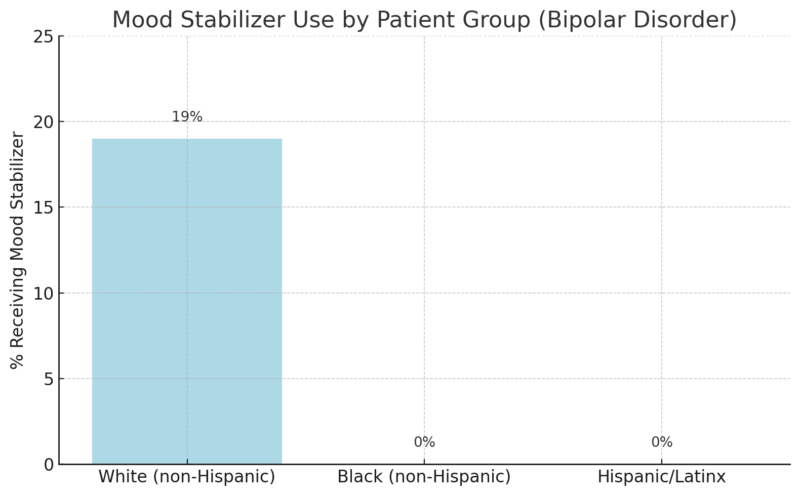

For example, mood stabilizers like lithium, valproate, or lamotrigine are cornerstone treatments for bipolar disorder. Yet research shows that minority patients are far less likely to be prescribed these evidence-based medications.

In one study conducted by Dr. K. McMaster and colleagues in 2014, only 17% of White patients with bipolar disorder had received a mood stabilizer in the past year – a surprisingly low figure on its own – but 0% of Black patients in the sample had received a mood stabilizer in that time. In other words, none of the Black bipolar patients were on proper medication, versus 1 in 6 of the White patients.

Another study in 2017 looked at Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic White patients and found a similar result: about 21% of White patients were taking a mood stabilizer, compared to 0% of Hispanic patients who were (literally none of the Hispanic bipolar individuals were on a mood stabilizer).

The researchers also noted that Hispanic patients were significantly less likely to even see a healthcare professional for a manic episode in the first place. These statistics are startling and point to deep gaps in care.

It’s also worth mentioning gender disparities in a different sense. While prevalence is equal, some studies suggest differences in how bipolar disorder manifests between men and women.

For example, women might have more mixed episodes or rapid cycling on average, and men might have more mania at first onset. Women with bipolar disorder are often initially misdiagnosed with unipolar depression (since they might seek help during a depressive episode and not be recognized as bipolar).

Men, as one statistic from DBSA noted, are sometimes misdiagnosed with schizophrenia more often, according to the dbsalliance.org. Additionally, women with bipolar disorder face unique challenges like mood exacerbations related to hormonal changes (e.g., postpartum mania risk).

Ensuring proper diagnosis (bipolar vs depression) in women is important – misdiagnosis as depression can lead to antidepressant monotherapy, which can trigger manic switches in bipolar patients.

To improve these disparities, experts recommend:

- Cultural competence training for providers to reduce bias and improve communication. Understanding how different cultures describe mood symptoms (for instance, using terms like “nerves” or somatic complaints) can help in accurate diagnosis.

- Diversity in the mental health workforce – having more Black and Hispanic clinicians could help patients feel understood and adhere to treatment.

- Patient education and community engagement: Trusted community organizations and leaders can help reduce stigma and encourage treatment. Psychoeducation about bipolar disorder in minority communities could help individuals recognize symptoms and seek care earlier.

- Improved access: Expanding Medicaid in all states and increasing low-cost clinics would disproportionately help minority patients. Also, integrating mental health into primary care (where many minorities might present) can catch bipolar disorder sooner.

- Standardized assessment tools: Using validated screening tools for mood disorders, regardless of race, might help counteract individual provider bias. For example, structured diagnostic interviews or mood questionnaires in primary care could flag bipolar symptoms that might otherwise be missed or mislabeled.

Trends Over Time and COVID-19 Impact

Pre-2020 Trends (2010s): Data from HCUP and other sources suggest that mental health hospitalizations for serious conditions (like bipolar and psychotic disorders) were relatively steady or slightly rising in the years leading up to 2020.

The Statistical Brief we referenced aggregated 2016–2018 data and noted, for instance, that mental disorders were among the top five reasons for hospitalization in younger adults by 2018, as noted by tac.org.

Specifically, for women aged 18–44, bipolar disorder was the fourth most frequent reason for any hospitalization (excluding childbirth) by 2018. This indicates that bipolar disorder’s share of hospital resources was significant and possibly increasing in younger women (it ranked just after depressive disorders and schizophrenia in that demographic).

The overall U.S. rate of bipolar hospital stays in 2016–2018 was about 83.6 per 100,000, as mentioned.

While we don’t have that exact figure from a decade earlier in this brief, other HCUP trend tables suggest that mood disorder hospitalization rates have not declined; if anything, they rose in the early 2000s (especially among youth and adolescents) and then plateaued or increased slightly for adults through the 2010s.

For example, one analysis found hospitalizations for bipolar disorder among youth increased fourfold from the 1990s to the early 2000s, puzzling experts and likely reflecting greater recognition and diagnosis in younger populations.

Among adults, the burden remained high through the 2010s. In summary, by the eve of the pandemic, bipolar disorder was a consistently large driver of psychiatric hospital utilization, with no clear downward trend in sight.

March 30 is #WorldBipolarDay.

Dr. Ayal Schaffer, head of the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program at Sunnybrook, shares insight on bipolar disorder during the pandemic and what individuals can do to help manage the disorder: https://t.co/Lam5YanGDn

— Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (@Sunnybrook) March 30, 2021

Impact of COVID-19 (2020–2021): The COVID-19 pandemic had profound effects on mental health in general, and these effects likely extend to people with bipolar disorder. Early in the pandemic, as lockdowns and social distancing took hold, there was a notable spike in mental health emergencies.

For instance, by mid-2020, emergency department (ED) visits for psychiatric issues (including suicide attempts) had increased significantly for both adults and children. Dr. Afzal, a psychiatrist at UChicago Medicine, reported that within a few months of the pandemic’s onset, suicide attempts and suicide-related ER visits “went up significantly”, and even completed suicide rates rose.

The WHO also found jumps in the prevalence of anxiety and depression nationally – one CDC brief noted a 25% increase globally in anxiety and depression prevalence during 2020.

While anxiety and depression are not bipolar disorder, the overall stress environment was elevated, which can precipitate mood episodes.

For individuals with existing bipolar disorder, the pandemic created a perfect storm of stressors and disruptions that could destabilize mood:

- Social Isolation: Lockdowns and social distancing cut people off from their usual routines, support networks, and coping activities. For many with bipolar disorder, maintaining regular social rhythms and support is important for stability. The isolation likely contributed to more depressive episodes in some, as well as removing buffers that might prevent the escalation of symptoms.

- Stress and Trauma: The fear of the virus, financial strain (loss of jobs, etc.), and grief (losing loved ones to COVID-19) all act as significant stressors. Stress is a well-known trigger for mood episodes. Indeed, surveys of bipolar patients during the pandemic indicated many experienced worsening mood symptoms or relapses under the stress.

- Interruptions in Care: In early 2020, many outpatient clinics closed or moved to telehealth, and patients might have had difficulty obtaining refills or seeing doctors in person. Some people with bipolar disorder may have fallen out of treatment during this time. Community programs, group therapies, and other resources were halted or went virtual, potentially leading to gaps in care.

Methodology

In this article, we take an in-depth look at bipolar disorder hospitalizations in the United States, focusing on which states experience the highest rates of hospital admissions for bipolar-related episodes.

We explored the prevalence and impact of bipolar disorder across demographics, ranked states by hospitalization rates (using the latest available data from sources like AHRQ’s HCUP), and identified regional “hotspots” where bipolar inpatient stays are especially prevalent.

We also examined disparities in diagnosis and treatment – for example, evidence of misdiagnosis in Black patients and under-treatment in minority communities – and how these inequities contribute to different outcomes.

Additionally, we analyzed trends over time (including data from 2016–2018 and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic up to 2025) and considered how health policies such as Medicaid expansion and state mental health funding influence hospitalization rates.

All findings are drawn from reliable, publicly available sources – including SAMHSA, RTI International, AHRQ/HCUP, CDC, the National Comorbidity Survey, and analyses by institutions like Johns Hopkins Medicine – and are fully cited.

By understanding the data and trends behind bipolar disorder hospitalizations, policymakers and healthcare leaders can better target resources and interventions to where they are needed most. In sum, this comprehensive review highlights the scope of bipolar disorder’s impact in the U.S., the stark state-by-state disparities, and the urgent need for strategies to improve outcomes for those living with this serious mental illness.

Conclusion

Bipolar disorder hospitalizations in the U.S. reveal a landscape of significant need, striking disparities, and opportunities for improvement.

We’ve seen that some states – notably Illinois, Nebraska, West Virginia, and Rhode Island – experience alarmingly high rates of people being hospitalized for bipolar episodes, indicating concentrated pockets of illness burden and perhaps better detection of cases.

Other states, like Texas, Washington, and Delaware, report unusually low rates, raising red flags that many individuals may not be receiving care until it’s too late (or at all). A closer look at regions uncovered hotspots in areas like northern Appalachia and parts of the Midwest, versus low-utilization zones in parts of the West and South.

These geographic patterns often mirror underlying socioeconomic challenges and the strength (or weakness) of local mental health systems.

In moving forward, a multi-faceted approach is needed. This includes:

- Strengthening early diagnosis (so fewer people spend years undiagnosed or misdiagnosed),

- Improving access to care regardless of geography or race (expanding insurance coverage, telehealth, and culturally competent services),

- Enhancing community support (housing, employment assistance, support groups which can reduce relapse triggers),

- Ensuring continuity of care after hospital discharge (to break the cycle of readmissions),

- Reducing stigma so that people are not afraid to seek help or adhere to treatment,

- Training providers to recognize bipolar disorder presentations in diverse populations (to address biases and knowledge gaps),

- Monitoring outcomes at the state and local level to identify emerging hotspots or gaps, especially in the wake of COVID-19.

This analysis underscores that bipolar disorder is not just a medical condition but a societal challenge that intersects with public policy, economics, and social justice. The disparities highlight where we need to do better to achieve equity in health.

Related Posts:

- Average GPA and MCAT Scores for Medical School Admission

- Black-Owned Businesses in the US. See Significant…

- A Tiny Chip the Size of a Grain of Rice Is Helping…

- Jaw Joint Disorder Research in 2026 - TMD IMPACT…

- Which States Have the Highest and Lowest Income Tax in 2025?

- US States With the Highest Homeowners Insurance…