A new study is drawing attention to a nutrient most people barely think about, choline, and its potentially powerful connection to brain aging, obesity, and early neurological decline.

The findings, published in Aging and Disease, suggest that low choline levels combined with obesity may accelerate pathways associated with Alzheimer’s disease long before symptoms appear.

As someone who follows metabolic and neurodegenerative research closely, I’m struck by how often these “minor” nutrients turn out to be central players in major health conditions.

Choline is known to be essential for liver function, cell membranes, and neurotransmitters. But this study elevates it from “important” to “possibly crucial for long-term brain protection.”

What the Study Found

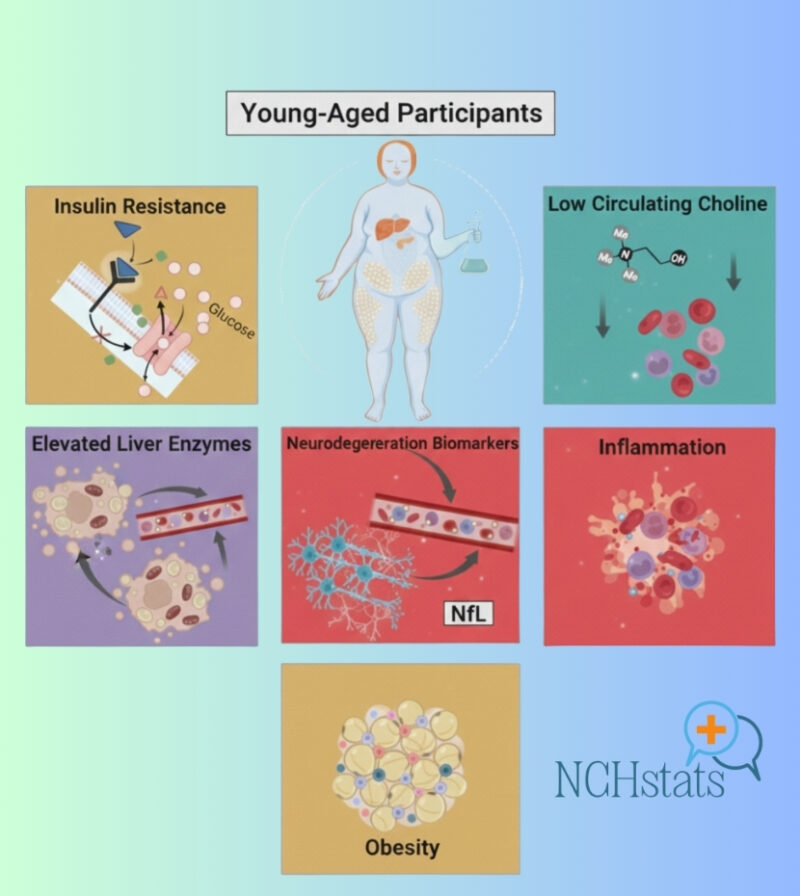

A team from Arizona State University recruited 15 adults with obesity and compared them to 15 metabolically healthy individuals. Despite the small sample size, the biochemical differences were stark:

- People with obesity had significantly lower circulating choline

- They also had higher inflammatory markers

- And, most notably, they showed elevated levels of neurofilament light (NfL), a blood protein that increases when neurons are damaged.

Researchers then examined post-mortem brain samples from older adults diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or mild cognitive impairment.

The same pattern reappeared: low choline linked with higher NfL, suggesting neuron injury even in early disease stages.

This does not prove causation, but the overlap across age groups and health states presents a compelling biological connection.

Why the Findings Matter

Lead ASU neuroscientist Ramon Velazquez says the results add to the growing recognition of choline as a “valuable metabolic and neurological marker.”

The team notes that new research published this month has already tied low choline to increased anxiety, memory problems, and metabolic dysfunction.

From a wider scientific perspective, this study fits into a long-running effort to untangle the relationships between diet, inflammation, adiposity, and neurodegeneration.

Alzheimer’s is rarely the result of one factor; instead, it tends to emerge from a mix of chronic metabolic stressors that slowly erode cognitive resilience.

Obesity is already considered a risk factor for Alzheimer’s; this work hints that choline insufficiency may help explain why.

Early Warning Signs? Or a Route to Prevention?

ASU behavioral neuroscientist Jessica Judd suggests that adequate choline may help protect neurons during young adulthood, creating a healthier foundation for aging brains.

If true, choline intake could become:

- A biomarker for early neurological vulnerability

- A preventive target for people at higher metabolic risk

- A modifiable lifestyle factor, unlike genetics or aging

The idea that a common nutrient, one we easily obtain from eggs, fish, poultry, beans, and cruciferous vegetables, could play a protective role is both promising and unsettling.

Promising because it’s actionable; unsettling because most people fail to meet recommended choline intake levels.

As ASU biochemist Wendy Winslow puts it:

“Most people don’t realize they aren’t getting enough choline.”

I have to admit, this hits close to home. Even while reading nutrition research daily, I rarely think about choline outside of prenatal health discussions.

This study made me check my own diet, and it probably should make many people reconsider theirs as well.

The Bigger Picture

The connection between obesity, inflammation, nutrient levels, and neurodegeneration has been hinted at for years. But studies like this one help clarify the biological “wiring” linking them.

What remains unknown:

- Is low choline causing neurological vulnerability?

- Does obesity deplete or impair choline metabolism?

- Could supplementation slow neurodegenerative processes?

- Would early choline monitoring help identify high-risk individuals?

Scientists don’t have clear answers yet, but the alignment of metabolic and neurological data signals a direction worth pursuing.

For now, the takeaway is straightforward: A nutrient most of us overlook may be more important for long-term brain health than previously understood.

Related Posts:

- Scientists Find a Way to Help Aging Cells “Swap…

- Shocking Study Finds No Link Between COVID-19…

- When Birth Rates Crash, So Do House Sales - The Hidden Risk

- Alzheimer's Disease in the US - 2025 Facts and Figures

- Could Lower Protein Intake Help Prevent Liver…

- A Tiny Gut Molecule Might Cut Type 2 Diabetes Risk,…