Researchers have identified exactly how an ultra-rare genetic mutation causes brain cells to die, and the mechanism appears strikingly similar to pathways implicated in major neurodegenerative diseases.

The work shows that mutations affecting the GPX4 enzyme trigger a specific form of programmed cell death called ferroptosis, driven by iron accumulation and oxidative damage to neuronal membranes.

The findings were demonstrated consistently across human patient-derived brain cells, lab-grown brain organoids, and mouse models, providing unusually strong evidence for a direct causal mechanism.

The study was led by scientists at Helmholtz Munich and published in Cell in December 2025.

A Disorder So Rare It Took Decades To Decode

Thank you @OdyliaTx for the spotlight and raising awareness about our efforts to #CureRaghav

Every patient with rare diseases deserve a better life! https://t.co/yzh1wZq4dK

— Sanath Ramesh (@sanathkr_) February 10, 2021

The human disease at the center of the study is Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia (SSMD), a devastating genetic condition first described in 1980.

Fewer than a few dozen confirmed cases have been documented worldwide. Children born with SSMD typically show severe brain and skeletal abnormalities, with many dying in early infancy.

Because of its rarity, SSMD has long remained poorly understood. Genome-wide sequencing over the past decade finally linked the condition to mutations in GPX4, a gene that encodes an enzyme essential for protecting cell membranes from oxidative damage.

What remained unknown until now was why defects in this enzyme are so catastrophic for neurons.

Why GPX4 Matters to Brain Cells

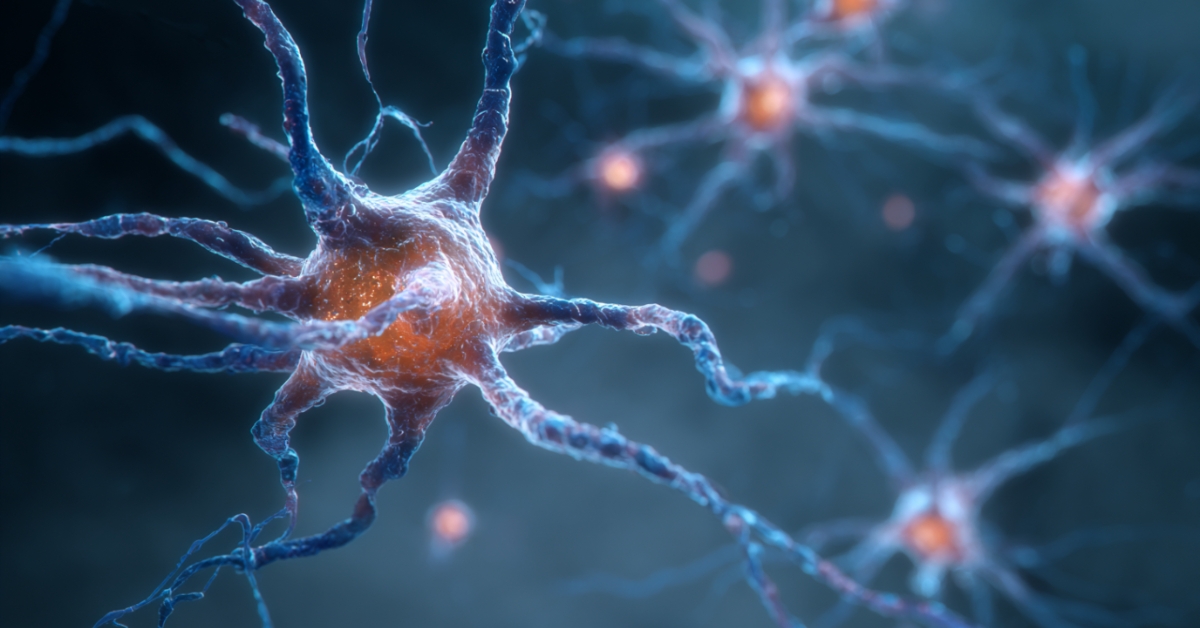

GPX4 is often described by cell biologists as a guardian against ferroptosis. Unlike other antioxidant systems that act broadly within cells, GPX4 has a highly specialized role: it neutralizes lipid peroxides directly within cell membranes, preventing them from reaching toxic levels.

In the new study, researchers focused on three children with SSMD who carried mutations affecting the same functional region of the GPX4 gene. Brain imaging revealed varying degrees of cortical atrophy, suggesting progressive neurodegeneration rather than a static developmental defect.

To investigate further, scientists recreated the mutation in mice and generated human neurons and brain organoids from the skin cells of an affected patient. Across all models, neurons failed in the same way.

Ferroptosis, not Inflammation or Protein Buildup

The neurons did not die through classical apoptosis or necrosis. Instead, they underwent ferroptosis, a regulated cell-death pathway driven by iron-dependent lipid damage.

Marcus Conrad, director of the Institute of Metabolism and Cell Death at Helmholtz Munich, uses a mechanical analogy to explain the failure. Under normal conditions, GPX4 is anchored into the neuronal membrane, where it continuously detoxifies lipid peroxides.

In SSMD, the mutation removes a small structural element that allows the enzyme to attach to the membrane.

Without that anchoring, GPX4 is present but functionally ineffective. Lipid damage accumulates, membranes lose integrity, and neurons die.

Crucially, this is not a downstream consequence of cell stress. The researchers show that ferroptosis is the initiating driver of neuronal death.

Why does This Matter Beyond a Rare Childhood Disease

Although SSMD itself is extraordinarily rare, the mechanism uncovered is not. Over the past several years, independent studies have linked ferroptosis to Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease.

Until now, it was unclear whether ferroptosis played a primary role or merely occurred as a secondary effect of ongoing degeneration.

This study strengthens the argument that membrane damage and lipid oxidation can sit at the start of neurodegenerative cascades, not just at the end.

Protein aggregates such as amyloid-β plaques have dominated dementia research for decades. The new findings suggest that oxidative damage to neuronal membranes may precede and possibly enable those later pathological features.

Blocking Ferroptosis Slowed Neuron Loss

One of the most clinically relevant findings came from intervention experiments. When researchers treated mice and patient-derived neurons with a chemical compound that inhibits ferroptosis, neuronal death slowed significantly.

This does not mean a treatment for dementia is imminent. However, it provides direct experimental proof that ferroptosis is not merely correlated with neuron loss but is mechanistically involved.

Svenja Lorenz, a cell biologist involved in the study, summarized the shift in perspective clearly: damage to cell membranes is not collateral damage. It is the event that sets degeneration in motion.

Childhood Dementia and What Rare Diseases Teach Us

Dementia is commonly framed as a disease of old age, but childhood dementia exists and is linked to more than 100 distinct genetic disorders. These conditions often progress rapidly, stripping cognitive function early in life.

Studying such rare cases offers an advantage that common diseases do not. Genetic causality is clear, timelines are compressed, and mechanisms can be isolated with fewer confounding factors.

In this case, a single missing structural element in one enzyme revealed a core vulnerability of neurons that may apply far beyond SSMD.

Why the Research Took 14 Years

The GPX4 mutation responsible for SSMD is subtle. It does not eliminate the enzyme. It alters its spatial behavior inside the cell.

Detecting that nuance required long-term collaboration between clinicians, geneticists, cell biologists, and imaging specialists across multiple countries.

As Conrad noted, connecting a microscopic structural change in one protein to a lethal human disease took nearly 14 years. The work underscores why slow, basic research remains essential for understanding complex neurological conditions.

Bottom Line

Scientists now know why this rare genetic mutation kills brain cells. Disabling GPX4’s ability to protect neuronal membranes triggers ferroptosis as a primary cause of neurodegeneration.

While SSMD affects only a handful of children worldwide, the mechanism uncovered points to a broader principle: oxidative damage to cell membranes may be a foundational driver of neuron loss across multiple brain diseases.

This shifts attention from protein buildup alone to the fragile lipid structures that keep neurons alive.