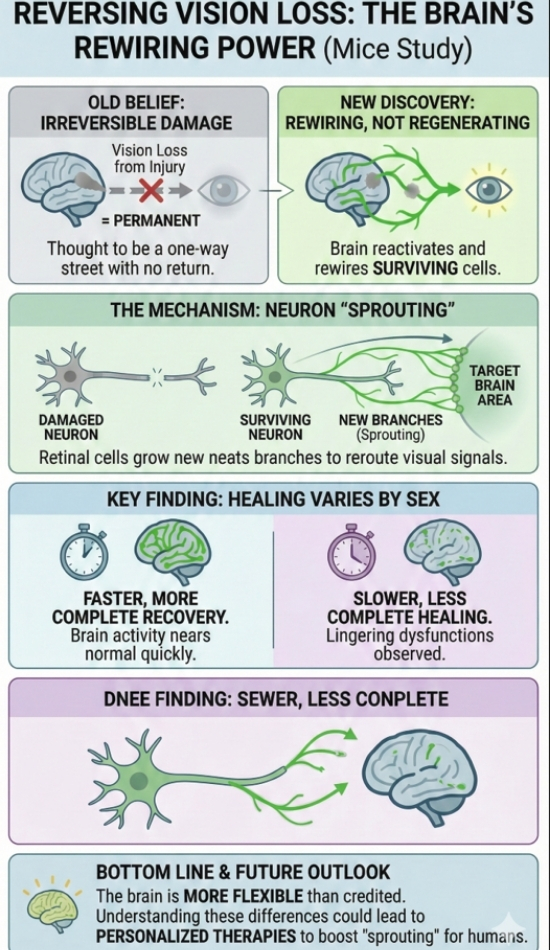

For decades, the loss of vision due to brain injury was seen as irreversible, a one-way street with no return. But a new study is flipping that long-held belief on its head.

Scientists have discovered that, under certain conditions, the brain can partially restore lost vision not by regenerating destroyed cells, but by reactivating and rewiring surviving ones.

The research, led by a team from Johns Hopkins University and published in JNeurosci, found that eye neurons can actually sprout new branches, forming fresh connections to the brain that help restore visual function.

In essence, the brain isn’t rebuilding from scratch; it’s rerouting, adapting, and healing in surprising ways.

A Brain That Bends, Not Breaks

For years, neuroscientists have wrestled with the frustrating limits of the central nervous system. Once neurons in the brain or visual system are damaged, the assumption was that recovery was minimal, if not impossible. But this study throws a wrench into that narrative.

Using mice as models, researchers observed a process called sprouting, where surviving retinal ganglion cells, the nerve cells that transmit visual signals from the eye to the brain, began growing new branches. These branches acted like detours, rerouting the traffic of visual information through alternate paths.

Instead of replacing the neurons that were lost, the brain appears to be reweaving its existing neural fabric, and in doing so, reclaiming some lost visual abilities.

Male and Female Brains Heal Differently

One of the more unexpected findings? The recovery process varied sharply between male and female mice.

Male mice showed a much faster and more complete restoration of their visual systems. Within just a few weeks, their neural connections had largely bounced back, and vision-related brain activity looked close to normal.

Female mice, on the other hand, experienced slower healing. Some never fully recovered, even months after the injury. The researchers observed lingering dysfunctions, which closely echo patterns seen in human patients.

This difference isn’t just a curious footnote; it could be a clue. Women are known to experience longer recovery times from concussions and other brain injuries, and this study suggests that biological sex might play a deeper role in how the brain repairs itself than previously thought.

Lead researcher Athanasios Alexandris emphasized that understanding these differences could lead to more personalized treatments for brain injury recovery in both men and women.

A Look Into the Future of Vision Therapy

While we’re still in the early days, this research points toward a promising new direction for restoring vision, and possibly other brain functions, after injury.

Scientists now want to understand what triggers sprouting, how to boost it, and whether this regenerative workaround can be applied to other areas of the brain. The idea is not to regrow what’s lost, but to work with what’s left, helping the brain create new routes around damaged areas.

Imagine a future where, after a traumatic injury or stroke, patients could undergo a treatment that stimulates their brain to rewire itself, restoring functions once thought permanently gone.

It’s not science fiction. It’s sprouting science.

Bottom Line

The brain might be more flexible and more self-healing than we ever gave it credit for. And thanks to a few resilient mice, we’re one step closer to understanding how to tap into that healing power.

Related Posts:

- A Groundbreaking Eye Treatment Just Restored Vision…

- Scientists Just Made Pancreatic Cancer Tumors Vanish…

- Here’s What Humans Could Look Like in 1,000 Years,…

- Scientists Just Found a Way to Regrow Cartilage…

- FDA To Make Food Additive Safety More Open - What…

- Can You Really Become a Nurse in Just 12 Months? 5…