Will the world’s population double by 2050, or could growth slow and halt far sooner than previously expected? A fresh analysis using advanced modeling and decades of United Nations data suggests that global population growth may peak as early as 2025, aligning with declining birth rates and the inevitability of a rising global death rate.

For years, demographers have projected future population growth using “principal components” methods, applying global fertility and mortality rates to the latest world population totals and projecting forward.

The United Nations offers three scenarios: a “high variant” projecting 28 billion people by 2150, a “medium variant” of 11.5 billion by 2075, and a “low variant” where growth peaks at 7 billion around 2050 before a gradual decline.

These scenarios have often felt like preparing for a blizzard, rain, and a heatwave simultaneously. The medium scenario is commonly treated as the “most likely” simply because it sits in the middle.

However, a least squares regression approach, which analyzes all past world population totals rather than relying on a single year’s data, offers a clearer and potentially more accurate forecast.

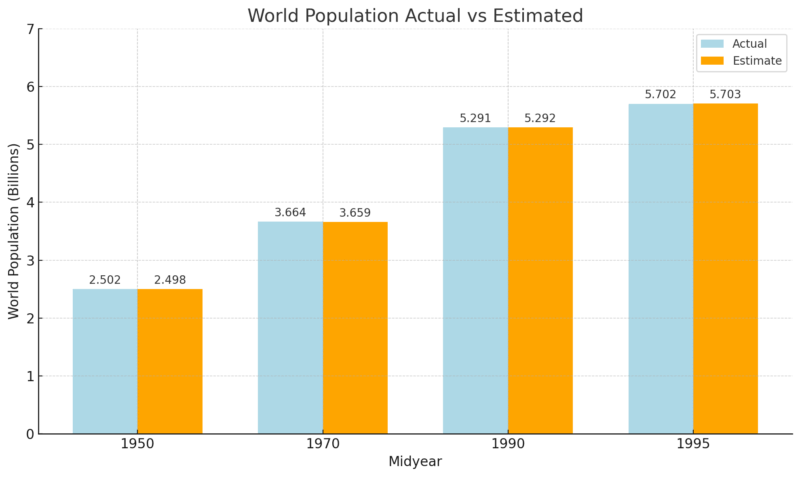

Using personal computing power to run these complex calculations, researchers compiled the most reliable UN Demographic Yearbook data from 1950 to 1990, dismissing outliers and averaging repeated estimates for accuracy.

For 1991–1996, they used the UN’s single published estimates and for 1994–1995, estimates from the Population Reference Bureau, ensuring continuity and precision.

This approach tested various growth models: straight-line, exponential, logistic, and convex (exponential growth at a decreasing rate). The convex growth model—producing a dome-shaped projection—showed the strongest correlation with actual historical data, achieving a near-perfect correlation coefficient of 0.99996 according to Research Gate.

On average, the difference between this model’s projections and actual population figures was just 7.9 million, a negligible margin at the global scale.

Based on this convex growth projection, global population growth is forecasted to peak at 7.07 billion around 2025, before entering a slow decline:

Such an unconventional forecast requires supporting evidence—and it finds it in the dynamics of birth and death rates. The world’s death rate currently stands at 9 deaths per 1,000 people per year, implying an unrealistic average life expectancy of 111 years if it continued.

Realistically, with life expectancy stabilizing around 75 years globally, the death rate would increase to approximately 13.3 deaths per 1,000, intersecting with declining birth rates around 2030.

This intersection suggests that the long-feared runaway population growth may never materialize. Instead, global birth rates are declining in many regions due to factors including urbanization, women’s education, and access to family planning, while the death rate is poised to rise simply due to biological limits on human lifespan.

The convergence of these trends aligns closely with the convex growth projection and the UN’s low variant, indicating that the global population could stabilize and begin to decline sooner than many governments and policy planners anticipate.

This shift carries profound implications for global economics, environmental planning, and social policy. Nations currently preparing for endless population increases may need to adjust strategies for infrastructure, food security, and aging populations in a world where the challenge may not be overpopulation, but rather a stabilizing or shrinking population.

As the world approaches what could be the end of its population boom, this new understanding urges policymakers, economists, and the public to rethink assumptions about the future—and prepare for a demographic transition that could reshape societies globally within the next generation.

Related Posts:

- This Secret Town Helped End World War II - Now 1 in…

- A Spoonful of Black Cumin Seeds May Improve…

- Caffeine in Your Blood May Influence Body Fat and…

- 11 Most Common Reasons for Divorce - Why Marriages End

- The World’s Largest City You’ve Never Heard Of - Why…

- Tennessee’s Population Growth in 2025 - Key Insights…