Transporting biohazardous materials is one of the most tightly regulated areas in global logistics. The risks are obvious: a single misstep can endanger public health, contaminate environments, and create legal liabilities.

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), more than 3 billion tons of hazardous materials are moved every year, and although most shipments arrive without incident, there are hundreds to thousands of hazmat incidents annually, many involving small non-bulk packages rather than tankers or rail cars.

In fact, a PHMSA (Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration) analysis of incident reports showed over 165,000 hazmat incidents related to non-bulk packaging compared with about 15,700 incidents in bulk packaging over a decade. These numbers highlight how, every day, small-scale shipments of biohazards are among the most vulnerable points in the chain.

For this reason, global authorities, from the World Health Organization (WHO) to IATA (International Air Transport Association) and PHMSA, stress a set of universal safety rules. Below are seven critical transport safety tips, explained in depth, with references to international guidelines, U.S. federal law, and real-world data.

1. Classify Materials Correctly

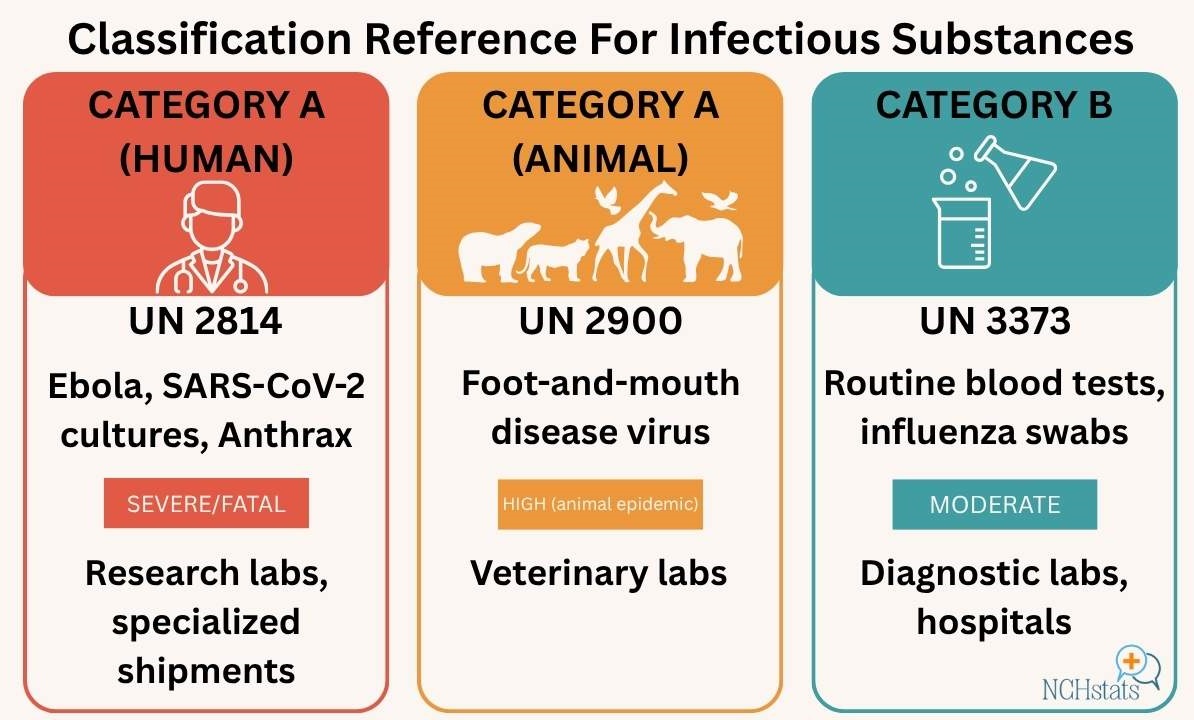

The most important step before packaging or labeling is proper classification. Infectious substances are divided into Category A and Category B, each with different regulatory requirements.

- Category A: Substances capable of causing permanent disability, life-threatening, or fatal disease. They are shipped as UN 2814 (human pathogens) or UN 2900 (animal pathogens). These include agents like the Ebola virus, SARS-CoV-2 cultures, or Bacillus anthracis.

- Category B: Substances not meeting Category A’s strict definition. These are common diagnostic samples, like blood or swabs for influenza, and are shipped as UN 3373, Biological Substance, Category B.

Misclassification is one of the most frequent errors seen by regulators. An infectious Category A culture incorrectly sent as Category B can result in improper packaging, missing paperwork, and exposure risks.

This is why classification should always be guided by a qualified biosafety officer and referenced against IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations and CDC/WHO guidelines.

2. Follow the Triple-Packaging System

Every infectious shipment must follow the triple-packaging principle, which is recognized globally. The system ensures that even if one barrier fails, others protect handlers and the public.

- Primary container: A sealed, leakproof tube or vial containing the specimen.

- Secondary container: A leakproof bag or rigid tube with enough absorbent material to soak up the entire sample if the primary fails.

- Outer container: A strong, rigid packaging that protects from impacts, punctures, and compression.

Category A packages must pass stringent performance tests like drop, puncture, stacking, and pressure resistance under 49 CFR §178.609, while Category B requires drop-test compliance under §173.199.

Using generic or non-certified packaging is a common mistake. Not only is it illegal, but it can also result in leaks during air pressure changes or rough handling.

Triple-Packaging Checklist

| Layer | Requirement | Regulatory Standard | Frequent Mistake | Best Practice |

| Primary container | Leakproof, sealed tube | WHO/IATA | Loose caps, brittle vials | Screw-cap tubes with O-rings |

| Secondary container | Must contain full spill | 49 CFR §173.199 | No absorbent material | Use absorbent sheets or granules |

| Outer container | Rigid, marked | 49 CFR §178.609 | Using weak cardboard | UN-certified rigid outer box |

3. Ensure Training and Certification of Personnel

No shipment can be safer than the people handling it. Regulations define anyone involved in classifying, packaging, marking, or shipping infectious materials as a hazmat employee. They must be trained under 49 CFR §172.704 and OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030).

Training includes four parts:

- General awareness – overview of dangerous goods.

- Function-specific – training tailored to actual duties (packing, documentation, handling).

- Safety – PPE, spill response, exposure management.

- Security awareness – preventing unauthorized access and misuse.

Recurrent training is required every 3 years under DOT and annually under OSHA. Inadequate training is one of the top five reasons for PHMSA enforcement penalties.

Training Reference

| Requirement | Frequency | Applies To | Consequences if Ignored |

| DOT hazmat training | Every 3 years | All hazmat employees | Civil penalties, shipment rejection |

| OSHA bloodborne pathogen training | Annually | Employees exposed to blood/OPIM | OSHA fines, worker injury |

| Records of training | 3 years | Employer | Non-compliance citations |

4. Label, Mark, and Document Accurately

Labels and paperwork are the language of hazmat safety. A shipment can be fully compliant in packaging but still rejected if the labels or documents are wrong.

- Category A: Requires the INFECTIOUS SUBSTANCE label, the proper UN number, and a Shipper’s Declaration for Dangerous Goods for air shipments.

- Category B: Requires the UN 3373 diamond mark, the words “Biological substance, Category B,” and the name/phone of a responsible person.

- Dry ice: Must have a Class 9 hazard label, “UN 1845,” and net weight in kilograms.

Documentation errors, like missing Shipper’s Declarations, are one of the most frequent causes of shipment delays and regulatory action.

Labeling Guide

| Shipment Type | Required Label/Mark | Paperwork | Common Failure |

| Category A | INFECTIOUS SUBSTANCE label + UN 2814/2900 | Shipper’s Declaration | Missing declaration |

| Category B | UN 3373 mark | Air waybill | Wrong or missing UN number |

| Dry ice | Class 9 hazard + UN 1845 + net weight | Waybill with weight | Omitting dry ice weight |

5. Manage Temperature Control Safely

Specimens often require refrigeration. The challenge is to keep them cold without creating new hazards.

- Dry ice (UN 1845): Sublimates to CO₂ gas. Without venting, pressure can build, causing packages to rupture. Regulations require vented packaging and labeling of the weight.

- Liquid nitrogen (LN₂): Extremely cold and must be shipped in vented dewars. Sealing LN₂ can cause explosions.

- Gel packs: Not regulated, but must be medical grade and tested for consistency. Household packs may leak or thaw too quickly.

Many incidents have been tied to the misuse of dry ice, especially in aviation. Correct labeling and vented packaging prevent both accidents and costly shipment rejections.

Refrigeration Methods

| Method | Hazard | Rule | Best Practice |

| Dry ice | Asphyxiation, rupture | UN 1845, Class 9 | Vent packages, label net weight |

| Liquid nitrogen | Explosive pressure | IATA PI 202 | Only in certified dewars |

| Gel packs | Leakage, thawing | Not regulated | Use validated medical-grade packs |

We asked prep center Dollan Prep Center for advice, and they told us:

“Most compliance mistakes we see aren’t about dangerous pathogens, but about the cooling method. Shippers forget that dry ice is its own hazardous material and needs labeling and reporting. Training staff to treat cooling agents as carefully as the biologicals themselves saves both fines and failed shipments.”

6. Maintain Chain of Custody and Security

Transporting infectious materials isn’t only about physical safety; it’s also about accountability. A broken chain of custody can mean lost samples, security risks, or regulatory violations.

Best practices include:

- Using tamper-evident seals with logged numbers.

- Documenting every handoff (lab to courier, courier to airline, airline to customs).

- Restricting access to trained and authorized staff only.

- Following the security plan requirements for higher-risk materials under 49 CFR Part 172 Subpart I.

In Europe, ADR (European Agreement on the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road) enforces biennial updates to maintain harmonized standards.

Chain of Custody Steps

| Step | Responsibility | Documentation | Risk if Skipped |

| Lab sealing | Lab staff | Seal log | Tampering, substitution |

| Courier pickup | Courier | Signed transfer form | Lost accountability |

| Airline acceptance | Airline DG desk | Acceptance checklist | Shipment rejection |

7. Prepare for Emergencies and Drill Regularly

Even with safeguards, spills, leaks, and exposure risks cannot be fully eliminated. Preparedness reduces the impact.

Every organization must maintain a spill response plan aligned with OSHA, DOT, and WHO guidance. This includes:

- Stocking spill kits with disinfectants, PPE, sharps containers, and absorbents.

- Training staff to isolate, disinfect, and notify authorities.

- Knowing when to escalate to DOT §171.15 immediate reporting (fatality, hospitalization, evacuation, or >$50,000 property damage).

- Practicing response with drills at least annually.

Emergency Preparedness

| Incident | Immediate Response | Reporting | Long-Term Action |

| Minor spill | Isolate, disinfect, PPE | Internal report | Review SOP |

| Major leak | Evacuate, notify DOT | §171.15 report | Revise training |

| Injury/fatality | Medical care, notify PHMSA | DOT F 5800.1 | Full investigation |

Final Word

Transporting biohazardous materials safely comes down to discipline in detail. The big accidents are rare, but small errors, wrong label, missing absorbent, untrained courier, happen daily and are responsible for most of the 180,000+ recorded hazmat incidents in the past decade.

By following these seven expanded safety steps, classification, triple-packaging, training, documentation, temperature control, chain of custody, and emergency preparedness, you align with global best practices and protect lives, property, and your organization’s reputation.

Related Posts:

- Is Mallorca Safe to Travel To 2025? Facts About…

- FDA To Make Food Additive Safety More Open - What…

- Smart Home Safety Market Reached Over 34 Billion…

- Top 13 Techniques for Improving Heart Rate Variability

- Top 4 Seasons With Record Denver Nuggets Attendance

- Top 10 Conditions That Lead to ER Visits in the U.S.…